Linda Thatcher

History Blazer, October 1995

The Utah landscape is dotted with hot springs resorts that have come and gone. Although a few remain, most are merely memories to aging Utahns. One such popular resort during the 1890s and early 1900s was Castilla Hot Springs in Spanish Fork Canyon, Utah County. The name Castilla was suggested either by the castlelike rock formations nearby or because the Spanish priest-explorers Escalante and Dominguez discovered the springs in September 1776 as they followed the Spanish Fork River down the canyon. They called it Rio de Aguas Calientes (“River of Hot Waters”) because of the hot springs flowing into the river.

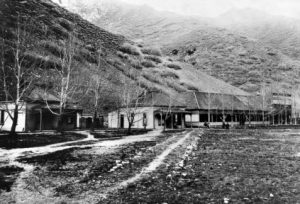

Castilla Springs, Spanish Fork, showing houses and stores, c. 1917. G. E. Anderson Photographer/BYU

In 1889, more than 100 years later, William Fuller filed for a patent on the hot springs property with the U. S. government. On the land he built a small house which contained a wooden tub for bathing in the mineral water. Later, the Southworth family became interested in the property. Mrs. Southworth, the family matriarch, felt that her health had been improved by bathing in water from the springs. She urged her two sons, Sid and Walter, to buy the springs to “make a resort for people who have hopeless afflictions, that they may come and be cured.” The Southworths obtained the land from Fuller and began to improve it. They filled the swampy area with gravel and built a three-story, red sandstone hotel. Other structures included indoor and outdoor swimming pools, a store, a dance pavilion, private bathhouses, several private cottages, and a saloon. Picnic areas, a baseball diamond, and stables were also provided.

During the summer months the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad ran excursion trains to Castilla. One of the most popular runs was the “moonlight excursion” from the Tintic Mining District in Juab County to Castilla. The train stopped at stations along the way to pick up passengers for an evening of dining and dancing.

Castilla Springs Hotel, 1917 in Spanish Fork. Cyrus E. Dallin and Family. G. E. Anderson Photograher/BYU Digital Image © 2009 Utah State Historical Society.

Besides providing recreation for many Utahns, the resort area was the site of several enterprises, including a cigar factory and a quarry that furnished silica used as flux by the Columbia Steel Company in Ironton, Utah. Nevertheless, the warm, sulfuric water remained the principal attraction at Castilla. Bathers came from far and near for the relief they believed they would find for such illnesses as rheumatism and arthritis. The springs’ water also became popular as a “cure” for other ailments such as alcoholism, chain-smoking, moral dissipation, and the “tendency to use profane language.”

In 1912 Sid Southworth died. Noted sculptor Cyrus Dallin, a native of Springville, helped his sister Daisy (Sid’s widow) financially with the resort. Eventually, he gained controlling interest in Castilla, but he had to rely on relatives to run it as he lived in Boston. The resort enjoyed a brief renewal of popularity in the 1920s, but by the 1930s it had fallen into disuse. Lack of funds and competition from other resorts contributed to its downfall.

In the 1940s a fire destroyed most of the hotel. What remained was eventually torn down. Today only a few ponds created by the springs mark the spot where the once-thriving resort stood.

See Linda Thatcher, “Castilla Hot Springs,” Beehive History 7 (1981).