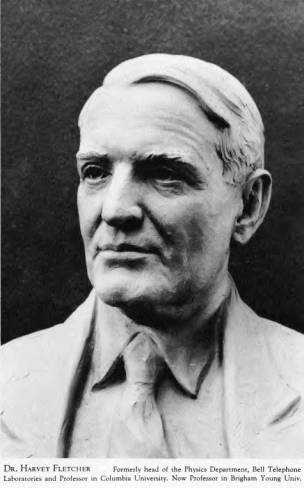

Dr. Harvey Fletcher. Formerly head of the Physics department, Bell Telephone Laboratories and Professor in Columbia University. Later professor at Brigham Young Univ. Nicholas G. Morgan, Donor.

A brilliant research physicist, Harvey Fletcher was called the father of stereo.

Anyone who likes movies or stereo recordings owes some of his enjoyment to the research of Harvey Fletcher. Those who can hear or speak with the help of a hearing aid or an artificial larynx also owe him a vote of thanks. An outstanding research physicist, teacher, and administrator, he deserved, many believe, at least part of a Nobel Prize.

Born on September 11, 1884, in Provo, Utah, to Charles and Elizabeth Fletcher, he attended local schools. He delivered groceries to pay for his tuition at Brigham Young University, graduating in 1907 and beginning a teaching career there. In 1908 he married Lorena K. Chipman, and they had five sons and one daughter.

Fletcher pursued doctoral studies in physics at the University of Chicago under Robert A. Millikan. He worked very closely with him on research that resulted in the first measurement of the charge on an electron, for which Millikan alone received the Nobel Prize in 1923. Practical applications of this research led to the invention by other scientists of the vacuum tube, which in turn opened up a new world of electronics.

After receiving a Ph.D. in 1911—the first physics student at the University of Chicago to graduate summa cum laude—Fletcher returned to teach at BYU. For five years the Western Electric Company of New York sent him job offers. He finally accepted in 1916 and worked for what became the Bell Laboratories until 1949.

His work at Bell led directly to high-fidelity recording, sound motion pictures, the first accurate clinical audiometers to measure hearing, the first electronic hearing aid (he was pleased that Thomas A. Edison wore one of his hearing aids), the development of the artificial larynx, improved telephone transmission, sonar, and stereophonic recording and transmission. He held more than 40 patents for acoustical devices, published more than 60 major scientific works, and received dozens of awards and honors, including a Presidential Citation from Harry S. Truman and membership in the National Academy of Sciences.

The accurate reproduction of sound so intrigued Fletcher that he devoted much of his life to it. In 1933 he created a stir when he demonstrated realistic sound reproduction in an auditorium. The audience was dumbfounded—and some became frightened and left—when airplanes apparently [p.13] flew from the stage and circled overhead. The famous conductor Leopold Stokowski cooperated with him in a demonstration of stereophonic sound transmission of a live performance from the Philadelphia Orchestra in Philadelphia to Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., where the sound was separated into three channels to achieve realism.

Under Fletcher’s able administration other researchers at Bell Labs thrived: three of them developed the transistor and received the Nobel Prize for this revolutionary device, and another created the semi-conductor. Other research he supervised now helps ground crews communicate with satellites and guide spacecraft. The development of color TV and advanced medical equipment are other areas in which Bell researchers under his direction made significant contributions.

Harvey Fletcher and Leopold Stokowski check equipment just before 1933 stereophonic transmission of live Philadelphia Orchestra to Washington, D.C. Improvement Era, July 1950. (is this a caption?)

From 1949 to 1952 Fletcher taught at Columbia University. Then he returned to BYU where he directed research and helped to set up a new Department of Engineering and the College of Physical and Engineering Sciences. He also researched musical acoustics, working well into his nineties with others to separate each component in the complex web of sound produced by the piano, organ, and string and percussion instruments.

He died July 23, 1981, after a stroke.