Dean L. May

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

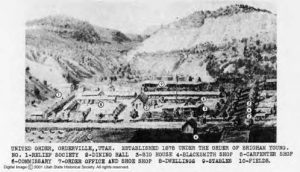

The united order, Orderville, Utah town was established in 1875 under the direction of Brigham Young. The structures are identified as: 1. Relief Society; 2. Dining Hall; 3. Big House; 4. Blacksmith shop; 5. Carpenter shop; 6. Commissary; 7. Order office and shoe shop; 8. Dwelling; 9. Stables; 10. Fields.

The United Order Movement was a program of economic and moral reform begun in 1874 under Brigham Young. It drew upon earlier efforts of the Latter-day Saints to organize cooperatives in Ohio and Missouri and though of little discernible impact in the 1870s, provided the ideological underpinnings for subsequent church poor relief, especially the Welfare Plan, organized in 1936. The return to a more communal economy is still widely regarded among Latter-day Saints as an essential step in preparing for Christ’s return and the principles of the United Order are central to present-day church governance.

The United Order was in large measure a response to specific problems that Young faced as leader of the Latter-day Saints in the early 1870s. The Utah economy had grown up in the 1840s, to the 1860s along essentially individualistic, capitalist lines: but tempered by strong elements of central control and communal idealism. Young and other church leaders, most notably his counselor in the First Presidency of the church, George A. Smith, and Apostle Orson Pratt, were concerned that changes attending completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 were pushing the Latter-day Saints away from their communal ideals and towards a more individualistic and capitalistic economic model. This concern led them to cast about for means of countering the materialism and selfishness that they saw as endemic to such a system. Young also feared the railroad would bring an increasing dependence of Utah upon outside products, diminishing the control of the Latter-day Saints over the region.

A precedent in Mormonism that seemed to offer a means of meeting these problems was Joseph Smith’s Law of Consecration and Stewardship, which had been practiced in Missouri in 1831-33 as the Latter-day Saints began to settle the area they called “Zion,” which was in Jackson County. Under the system, communicants consecrated all their possessions to the church in exchange for a “stewardship”–a home and the resources needed to practice their chosen trade. They were then to use their initiative to manage and improve upon their stewardship. They accounted to the bishop once a year, consecrating at that time any surplus beyond family needs their efforts during the year had accrued. At the same time, Joseph Smith and other church leaders in Ohio began management of several manufacturing enterprises in behalf of the community, calling the collective management system at times the “United Order.”

Consecration and Stewardship ended as the Latter-day Saints were driven from Jackson County in 1833, and only sporadic attempts were made to put its principles into operation during the rest of Joseph Smith’s lifetime. The United Order in Ohio, part of the larger Consecration and Stewardship system, collapsed at the same time because of internal mismanagement and a generally unfavorable economic climate. Brigham Young, one of the first apostles chosen by Joseph Smith, was nonetheless greatly influenced by his memory of these communal endeavors under Smith. That memory helped persuade him in the 1870s to conclude that the time was right for the Saints to move in the direction of economic cooperation.

Young’s wish that spiritual and temporal interests of the Mormons be combined had already found a promising model in cooperatives founded in the mid-1860s in the Utah towns of Lehi and Brigham City. Following these examples, in 1868, he founded Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution, a church-sponsored retail trading system that he hoped would drive out non-Mormon merchants and be profitable enough to provide the capital needed to foster local cooperative industries. With the Salt Lake City ZCMI as a central wholesaling facility, Young encouraged the establishment of some 150 retail branches in almost every Mormon town and village.

Despite the apparent short-term success of ZCMI, Young still wrestled with the problem of keeping the Saints apart culturally and economically from the incoming flood of Gentiles attracted by gold and silver strikes in Utah’s mountains. The Panic of 1873 provided a particularly sharp lesson in the dangers of integration with the national economy. Those areas of Utah tied to mining suffered severely, while Brigham City, with its elaborate cooperative system, seemed relatively unaffected. Observing poverty, dispiritedness and disaffection as he traveled south to his winter home in St. George during the winter of 1873-74, the aging Mormon leader considered how best to control the situation. The previous October Lorenzo Snow, apostle and founder of the Brigham City Cooperatives, had preached a sermon which perhaps was still ringing in Young’s ears: “It is more than forty years since the Order of Enoch was introduced, and rejected. One would naturally think, that it is now about time to begin to honor it.”

Using the name from the cooperative manufacturing effort instituted under Joseph Smith, Young began in February urging each settlement to organize under the “United Order of Enoch.” So important was the new movement that Young postponed the April general conference so he could be in Salt Lake City to introduce personally the new system of economic reform. As enthusiasm for the movement grew, many Mormons were rebaptized to indicate their commitment to the order. Church leaders replaced reluctant bishops, and sent envoys to remote areas to deal with foot dragging or problems arising from the order. The church printed broadsides of the “Rules…of the United Order,” which were posted in ward meetinghouses, committing members to general moral reform as well as to living the communal order.

By the next fall, some two hundred united orders had been founded at least on paper, among both rural and urban congregations. Yet only here and there was attachment to the program sufficient to sustain the effort beyond the 1874 season. Many never got beyond the stage of electing officers. The disappointing result perhaps could have been predicted. Young was attempting at a stroke to transform a frail but functioning capitalist economy, serving some 80,000 persons into a commonwealth of communes. Aware that some would resist, he specifically ordered that no one be coerced. Moreover, he placed upon the bishop of each congregation the responsibility of determining how far his flock was willing to go in the direction of cooperation and urged bishops not to push them further than they were willing. The result was a bewildering variety of organizations and a good deal of fighting within congregations as to what form their United Order should take. In no instance was the specific form of Smith’s earlier Law of Consecration and Stewardship followed.

Northern communities, such as Brigham City, a number of which already had well-developed community cooperatives, merely changed the name of their organization and continued business as usual. Many of the city congregations in Salt Lake, Ogden, and Provo, after some stumbling, attempted to found a manufacturing enterprise, contributing capital and labor to establish a community-owned meat market, hat factory, or soap factory, for example. Yet city bishops were perhaps of all Young’s lieutenants most tied to the Gentile economy, and most were not eager to lead their flock into the United Order. Only two or three of the city wards formed viable organizations.

The more common orders were in the congregations of rural towns, such as at St. George, where land and farm equipment were placed under the direction of an elected committee which supervised production. The committees decided such matters as which crops to grow, who should work at which tasks, and to what extent members would be allowed to move or work outside the order. There was, however, no effort to prescribe common dress or uniform housing, to eat at a common table, or to regiment personal lives, beyond seeing that the work due the order was accomplished. Moreover, as the orders began to disband in the fall of 1874, the members seemed to have no difficulty identifying the property they had contributed.

Another form of united order was urged by those who felt a fully communal life would be the only one consistent with Brigham Young’s aims. Their devotion to what was called the “gospel plan” was such that in at least two instances severe strains developed between the communalists and those desiring something less than an all-encompassing cooperative. In Kanab, the bishop suspended the sacrament (communion) for several months because there was such rancor between the two camps. The breach became so great in Mt. Carmel that it could not be healed. Those favoring the gospel plan seceded from the town in 1875 and founded their own two miles away, which they named Orderville. Orderville became the symbol for the most communal United Order and a model for a number of Orders, especially in the southern portions of Mormon country.

The Orderville Saints went far beyond what Joseph Smith had envisioned in the Law of Consecration and Stewardship. The members ate together in a common dining hall, wore uniform clothing made by Orderville industries, and lived in uniform apartments. The elected board supervised all activity, including entertainment, schooling, cooking, clothing manufacture, and farming. Private property did not exist, though personal possessions were assigned as a Stewardship to each individual.

Under this regimen the order prospered, both materially and spiritually. Assets of the eighty families tripled from $21,551 to $69,562 in the first four years of operation and reached nearly $80,000 by 1883. The leaders made adjustments as time went on. In 1877 they replaced the earlier loose dependence upon willingness to contribute with an accounting system that placed uniform values on labor and commodities (the wages varying by age and sex, but not type of work). A flood in 1880 destroyed the dining facilities, ending communal meals. In 1883 Erastus Snow, a regional church official, recommended moving to an unequal wage and partial stewardship system, the latter giving each family a plot of ground to till for its own use. Evolution away from the original communal purity continued as specific enterprises were leased to their operators for a fee retained by the order.

External pressures took their toll as well. The largely polygamous leadership of the community was decimated after the U. S. Congress passed the Edmunds Act of 1882. This act stimulated a vigorous campaign to enforce federal anti-polygamy statues, leading to the imprisonment or forced exile of many local leaders. In 1885 central church leaders, eager to reduce the range of federal complaints against Mormon peculiarities (the government was hostile to Mormon economic as well as marital practices), counseled the members to disband the Order, which they agreed reluctantly to do. They retained community ownership of the tannery, woolen mill, and sheep ranch until 1889 and finally let the corporation lapse in 1904.

Although the less communal stock company system of Brigham City was at least as successful financially as was Orderville, it did not capture the imagination and live on in the collective memory of Mormons. Orderville became the symbol of the United Order for subsequent Saints, a daring and near-successful effort to build the City of God on earth. Celebrated in song and legend, Orderville is in the minds of most Mormons today a model of selflessness, devotion and future obligation. In fact few today seem to realize that the United Order of Enoch was attempted outside of Orderville.

Sporadic efforts were made in the 1880s to implement some form of the United Order, especially in the founding of new colonies, and of course some organizations, such as Orderville and Brigham City, continued for a decade or more after founding. Yet it was clear by 1876 that the mass involvement Young had hoped for would not materialize. Asked in the last year of his life if he had launched the effort on his own or through revelation, he replied that he “had been inspired by the gift and power of God to call upon the Saints to enter into the United Order of Enoch and that now was the time, but he could not get the Saints to live it and his skirts are clear if he never says another word about it.”

Faced with unremitting federal pressures towards conformity, Young’s successors were content to retreat from advocating an active communal life and to nourish the substance of communalism that would remain central to Mormonism. Southern Utah leader Erastus Snow advised those who regretted the demise of the Order to, “Murmur as little as possible; complain as little as possible, and if we are not yet advanced enough to all eat at one table, all work in one company, at least feel that we all have one common interest and are all children of one Father; and let us each do what we can to save ourselves and each other.”

It perhaps is no surprise that the United Order experience did not turn the Mormons against the communal values that had so long been important to their identity as a people. On the contrary, the regret in Brigham Young’s complaint that he “could not get the Saints to live it” and the promise in Erastus Snow’s observation that “we are not yet advanced enough” resonated long in Mormon country. Mormons continued to call church assignments “stewardships” and to vow to consecrate all their energies and possessions to the church. They drew upon the idealism that was part of the United Order experience in founding their Welfare Plan in 1936, and continue to catechize themselves with the question of whether they would have the faith to live the United Order as a final step in preparing for Christ’s return. A blueprint for a perfect society could be readily forgotten, but not a failed effort to build it.

See: Edward J. Allen, The Second United Order among the Mormons (1936); Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830-1900 (1958); Leonard J. Arrington, Feramorz Y. Fox, and Dean L. May, Building the City of God: Community and Cooperation Among the Mormons (1976); Lyndon W. Cook, Joseph Smith and the Law of Consecration (1985); Joseph A. Geddes, The United Order Among the Mormons (Missouri Phase) (1924); Robert B. Flanders, Nauvoo: Kingdom on the Mississippi (1965); Dean L. May, “Brigham Young and the Bishops: The United Order in the City.” New Views of Mormon History: A Collection of Essays, ed. By Davis Bitton and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher (1987); Wallace Stegner, The Gathering of Zion: the Story of the Mormon Trail (1971); Evon Z. Vogt, Ethel M. Albert, eds. People of Rimrock: A Study of Values in Five Cultures (1966).